I am fascinated by him. Maybe meaning itself can be found in meaninglessness. Jarry defines pataphysics as “the science of imaginary solutions.” In a world where anxiety and uncertainty are constantly increasing, Bosse-de-Nage’s absurdity and laughter feel surprisingly relatable. In the midst of confusion and unpredictability, imagination and humor become ways to engage with reality and make sense of it.

I titled the series Ha-ha. In these works I did not recreate the story scene by scene. Instead, I took Bosse-de-Nage and fragments of text from the book and merged them with the time and space I inhabit now, including Peter Rabbit’s little jacket, ducks in the park, aliens, pastures, zoos, sculptures, and gods. This continues Bosse-de-Nage’s adventure and lets his absurd journey collide with the real world in unexpected ways.

Bosse-de-Nage 是一只 dogfaced baboon,一半脸是蓝色的,另一半是红色的。他出自法国作家 Alfred Jarry 的小说 Exploits and Opinions of Dr. Faustroll, Pataphysician,是博士的随从,从巴黎出发,前往无数奇异的岛屿。Bosse-de-Nage 唯一会说的话是 “Ha-ha”,无论他开心或难过,活着或死亡,他都只说这句话。有人说,他用荒诞的行为嘲讽现实的严肃性和逻辑性;也有人认为他代表虚无,因为他从不做任何解释,即便在被杀死的瞬间,他也只是张开嘴,留下一个“Ha-ha”。

我被这个角色深深吸引,或许无意义本身就是一种意义。有趣的是,Jarry 对 pataphysics 的解释是 “the science of imaginary solutions”。在焦虑和不确定感日益增加的当代社会,Bosse-de-Nage 的荒诞与笑声反而显得格外贴近现实。在混乱和不可预知之中,想象力与幽默既可以作为现实的对照,也可以成为理解和应对现实的方式。

我将这个系列命名为 Ha-ha.。在这些作品中,我没有逐帧复现故事,而是把 Bosse-de-Nage 和书中的文字碎片提取出来,与我当下所处的时空融合:彼得兔的小衣服、公园里的鸭子、外星人、牧场、动物园、雕塑、神……以此延续 Bosse-de-Nage 的冒险,让他的荒诞旅程与现实世界产生奇妙的碰撞。

Bosse-de-Nage Running Through Wild Grass, With Sandcastles and Fiery Orbs Mirrored in Water

/Bosse-de-Nage奔跑在茂盛的野草中,在水面的倒影中看见沙砾堆砌的城堡和燃烧的火球

2025

oil on canvas

120x160cm

Bosse-de-Nage Rowing Across a Make-Believe Lake, Beneath the Silent Witness of Foxgloves and Ducks

/Bosse-de-Nage在毛地黄和鸭子的见证下从假水上划过

2025

oil on canvas

120x160cm

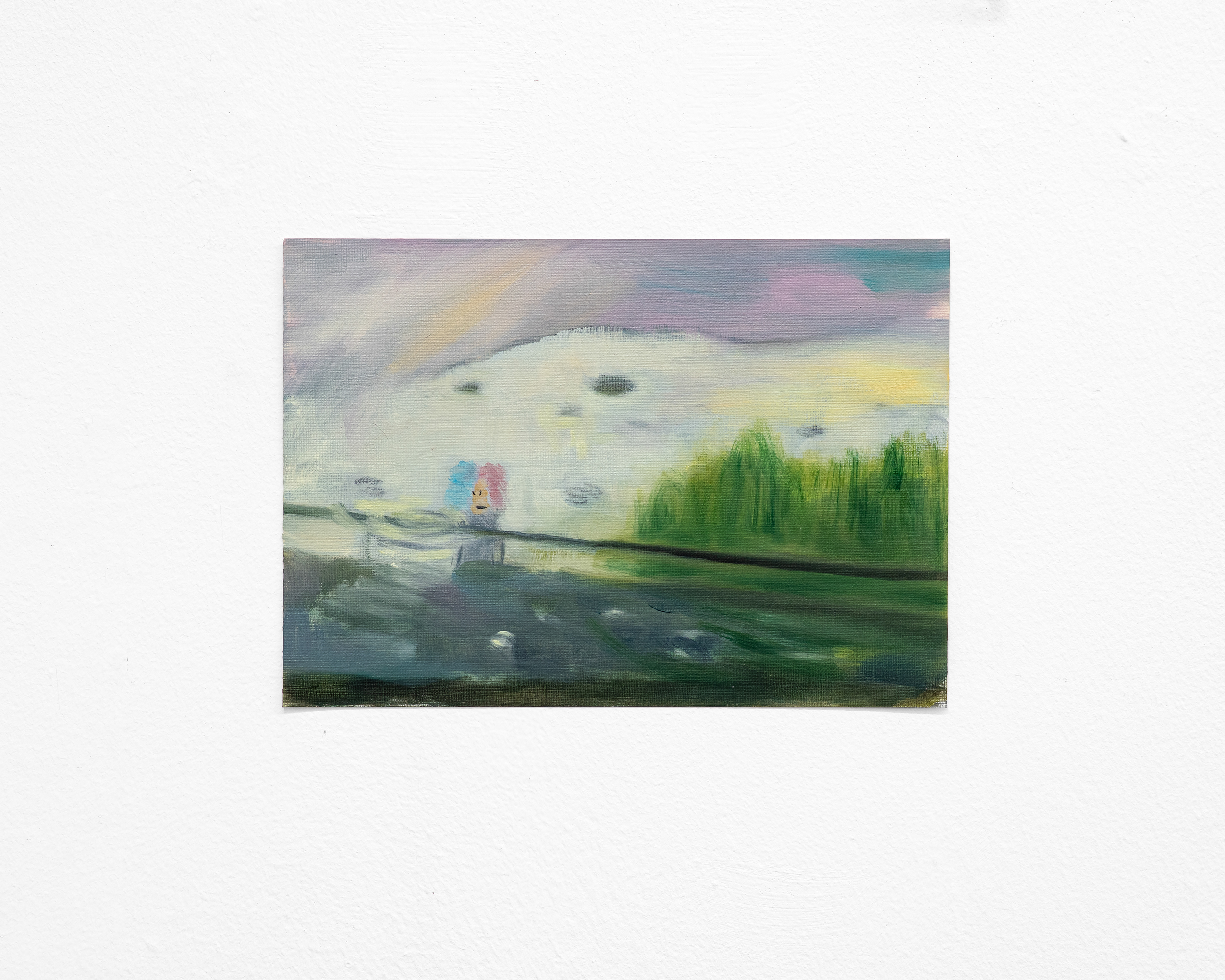

Bosse-de-Nage Swimming Through the Still Pond of the Botanical Garden

/Bosse-de-Nage在植物园的水塘里游泳

2025

oil on canvas

50x80.9cm

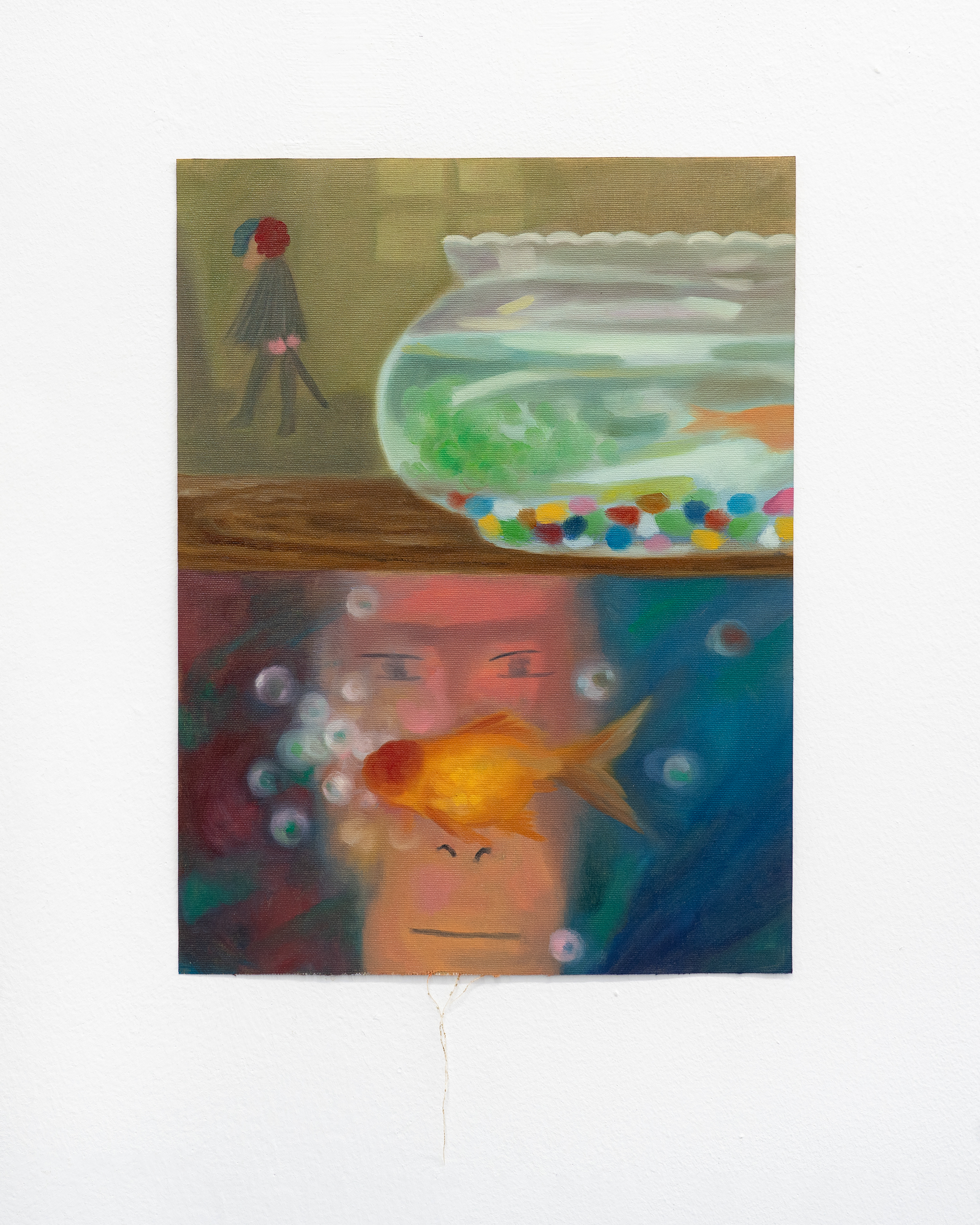

Bosse-de-Nage Beholding a Solitary Statue

/Bosse-de-Nage看见了一座雕像

2025

oil on canvas

50x80.9cm

Bosse-de-Nage Wandering by the Night Lake/

Bosse-de-Nage在夜晚的湖边散步

2025

94 x 49 cm

oil on canvas

Bosse-de-Nage Born from a Seashell, Welcomed by Angels as Waves Crash Against the Rocks/

Bosse-de-Nage从贝壳中诞生,海浪拍打着礁石,天使迎接它

2025

oil on canvas

60 x 80 cm

“Pataphysics is the science of imaginary solutions.” — Alfred Jarry

Science, as we understand it, is the systematic study of the natural and social world that begins with observation, leads to patterns, and becomes common sense. Through experimentation and countless tests, it finally condenses into a clear theory, a perfect formula. Yet the world today seems ever less orderly, resting on layers of theory that feel intangible and hollow without the guidance of context and sanity.

Similarly, Meng Donglai’s world has no generalities – only particulars – each rendered with the impression of a dream. Her paintings unfold like chapters from a novel: absurd, empirical, and tender all at once, where the boundary between reality and the imaginary dissolves into a single hybrid persona: a dog-faced baboon, as seen in Alfred Jarry’s Exploits and Opinions of Dr. Faustroll, Pataphysician.

The artist’s fascination with Jarry, a pioneering French writer best known for his scandalous play Ubu Roi and the invention of ‘pataphysics, “the science beyond metaphysics,” through a chance discovery: she encountered the book in a museum of curiosities filled with taxidermy animals and impossible specimens, not far from London Fields. Inspired by her summer in London this year and the novel’s fantastical plots, Meng conjures a central figure for her new series, Haha, taking its name from Bosse-de-Nage – the baboon who accompanies Dr. Faustroll through Jarry’s book. The baboon’s only utterance, ‘Ha ha,’ is both laughter and echo – a sound that hovers between meaning and meaninglessness, commenting on the absurdity that prevails across eight imagined chapters.

Meng paints not the events of this story, but the diagrams of the illogical, equations that solve nothing, a novelistic universe where a baboon, a scientist, and a bureaucrat travel in a perforated boat miraculously capable of staying afloat. More importantly, she paints the psychic intervals between them – the pauses, the unease, the faint afterglow of a laugh that has already gone cold. Her images oscillate between cruelty and affection, farce and faith, distance and desire. In one work, a baboon is born from a shell like Botticelli’s Venus, greeted by angelic creatures who bring no revelation except irony. In another, two horses appear at a café frontier, trying to lick a croissant through a glass veil. Elsewhere, a UFO shines a beam of light, as if receiving a lost child back into a safe yard.

The word pataphysics mocked the modern obsession with reason. It reminds me of an ancient Eastern philosophy, or rather, a mode of being: the art of appearing naïve while seeing through everything. In Meng’s cosmology, punts, hot air balloons, sandcastles, and statues coexist with mythic animals and uncanny landscapes. The gestures of painting merge with gestures of play, erasing the boundary between art and non-art, between the solemn act of making and the leisure of daydreaming. Meng’s figures drift through a theatre of contradictions, standing in an in-between space where cause and effect collapse, and the most irrational premise becomes a rigorous proof.

For Meng, this absurd refrain becomes a way to speak through silence and a language that replaces explanation with wonder. She calls these paintings “immersive daydreams.” They do not depict the world but test its permeability. Each image asks whether what we encounter is external reality or a projection of our longing. The baboon’s wandering becomes a philosophy of escape, not from the world itself, but from the obligation to make sense of it.

There is humour here, but it is heavy with melancholy. The laughter of Haha, both a name and a sound, reverberates through the paintings as a rhythm of estrangement, a recognition that what cannot be understood might still be loved. Everything is particular, nothing is general. And in that unrepeatable strangeness, Meng Donglai’s world feels uncannily like our own – only more truthful, as it never pretends to be real.

Text by Yiren Shen

(Yiren Shen is an independent writer based in Oxford, United Kingdom)

→